While they might not look like a DeLorean, cells dividing in a dish help scientists look backward and forward in time. Researchers developed a new tool called Rewind that allows them to identify rare cells that will become resistant to drug treatment in a population of genetically identical cells. This new technique will help scientists and clinicians identify cancer cells that may become resistant to treatment and answer fundamental questions like how cells develop.

“A lot of the focus has been on how cancer cells can vary genetically,” said Benjamin Emert, an MD-PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania and first author of the Nature Biotechnology study.

But in recent years, “It's become very evident that even genetically clonal cells — cells that are very closely related and presumed to be genetically nearly identical — can vary dramatically in terms of gene expression, as well as their chromatin accessibility, or histone modifications,” he added. “They can vary in almost any way imaginable.”

In some cancers, there are rare cells that are “primed” to become resistant to a particular drug, likely due to differences in the expression of different genes. Emert and his colleagues developed Rewind to find these rare cells and figure out what factors caused their drug resistance.

Rewind works by inserting a unique DNA barcode into cells before treating them with a drug. When the cell divides, it passes on the barcode to its daughter cells. After the cells divide for a few generations, the scientists divide the population in half, fixing one half as a “Carbon Copy,” and treating the other with a drug.

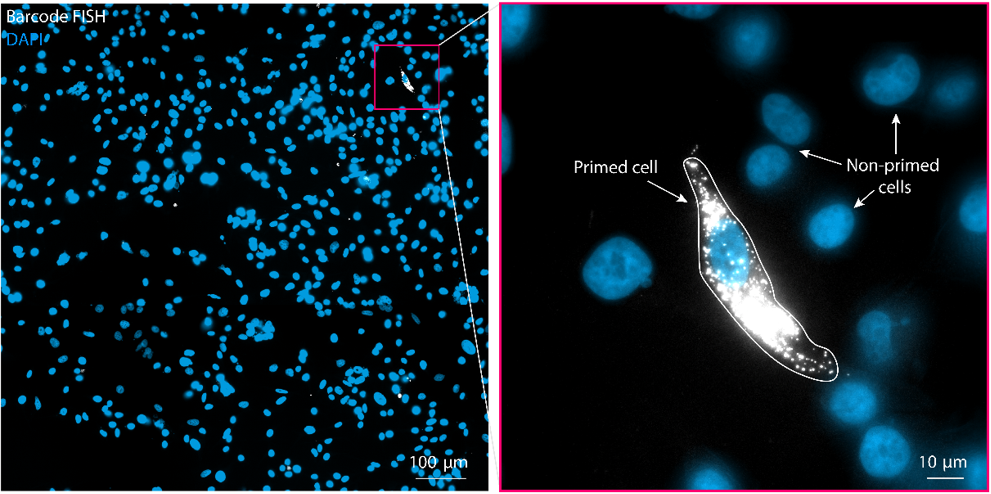

After a few weeks, drug-resistant cells emerge and dominate the population. The team sequences the barcodes of the resistant cells and generates matching RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probes that emit light when bound to RNA. When the scientists apply the probes to the cells in the Carbon Copy population, only the “twins” of cells that became resistant light up with a matching barcode.

“We can scan through millions of cells to find only those rare cells that are effectively the twins of the cells that became resistant,” Emert explained.

From there, scientists can analyze features like the gene and protein expression of the primed cell in the Carbon Copy population to investigate why it became resistant.

When the team used Rewind on a melanoma cell line, they identified approximately 200 genes that were differentially expressed between primed cells that became drug-resistant and those that didn’t. Of these genes, they looked at 9 marker genes, which showed distinct expression differences in primed vs non-primed cells. Interestingly, slight differences in expression of these marker genes led to differences in the level of drug resistance exhibited by cells that became resistant.

Ido Amit, an immunologist at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel who was not involved in the research, thought that the study represented an exciting breakthrough in the field.

“The ability to actually see the data and really understand that this heterogeneity within the cancer drives the tumor resistance is something very exciting. And I think it perhaps can bring new thinking of how we would actually treat this tumor in a very different way,” he said.

Emert is also excited to see how this technology might be useful in cancer diagnostics and in better understanding how cells determine their fate.

“There're a lot of interesting phenomena in biology [that] seem to arise from rare populations of cells,” Emert said. “It's often the case that these are just very fascinating, but also frustratingly difficult and challenging because of the rarity [with] which they occur.”

With a new way to find these rare cells, all scientists need to do to study them is take a step back in time.

Reference

Emert, B.L., Cote, C.J., Torre, E.A. et al. Variability within rare cell states enables multiple paths toward drug resistance. Nat Biotechnol (2021).