Patent Docs: Patent interference parties provide evidence for priority

The arguments over "first to invent" and ownership of CRISPR tech continue

CRISPR (an acronym for Clustered Regularly lnterspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) is a powerful and potentially very lucrative technology, permitting genetic manipulation in medicine, agriculture, and many other applications. At least in part due to its commercial potential, the battle for inventorship of this technology (which determines ownership, at least in this case) has been worth the fight, specifically between The Broad Institute, Harvard University, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (aka, “the Senior Party” or “Broad”) and The University of California/ Berkeley, the University of Vienna, and Emmanuelle Charpentier (aka, “the Junior Party” or “CVC”).

This battle has been joined twice in a patent proceeding termed an interference and the present one has resulted in the parties making their case for being “first to invent.” An earlier interference was terminated without resolution of the inventorship question on the grounds that CVC had not shown its patents encompassed eukaryotic versions of the CRISPR methodology. As a consequence neither party was required or had the opportunity to show its earliest invention dates until now. But in that earlier interference neither party was deprived of its patents, their being held to be directed to “patentably distinct” and therefore separately patentable inventions. Here, the stakes are considerably higher, because the outcome will result in the losing party losing its patents involved in this interference.

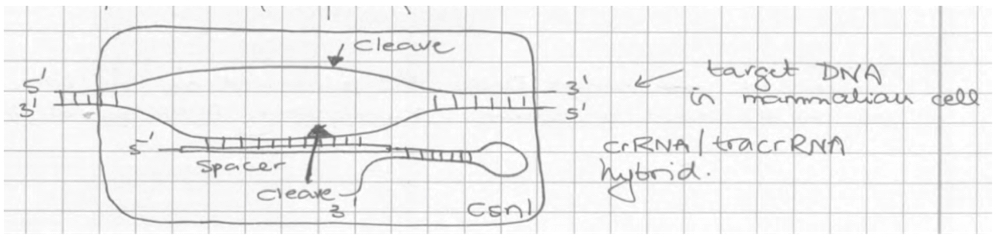

CVC as Junior Party bears the burden of proving its inventors (including 2020 Nobel Prize winners Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier) were the first to invent methods for using CRISPR in eukaryotic cells. Pursuant to conventional concepts of proving invention, in its motion for priority filed before with Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) on October 31st CVC asserted that its inventors had conceived of the use of a version of CRISPR comprising the bacterial nuclease Cas9 and a single-guide RNA molecule on March 1, 2012, with further revisions of the concept on April 11, May 28, and June 28, 2012, and that these inventor had reduced the method to practice several times on August 9, 2012, and thereafter on October 31, November 1, 5, and 18, 2012. These assertions were supported by contemporaneous records and evidence showing laboratory notebook pages such as:

Importantly, in view of the outcome of the earlier interference between the parties and as it turns out Broad’s arguments in its priority motion, CVC argued that this conception was sufficient for its inventors to be deemed the first to invent because actually reducing the invention to practice required only the exercise of “ordinary skill” that led to a predictable result. The motion asserted evidence for successful practice of the inventive CRISPR methods in zebrafish cells (resulting in genetically modified zebrafish); this evidence had been included in the CVC patent application that provided the earliest priority date recognized by the PTAB in the interference.

The evidence also included successful application of eukaryotic CRISPR methods in experiments using human cells in November 2012. CVC provided corroboration of its arguments (as required in an interference) with documentary evidence and testimony of witnesses (in addition to the inventors, whose testimony carries no weight in an interference) with contemporaneous knowledge of the facts and events surrounding invention. CVC’s motion also provided evidence from witnesses that suggested Broad had not invented independently of CVC.

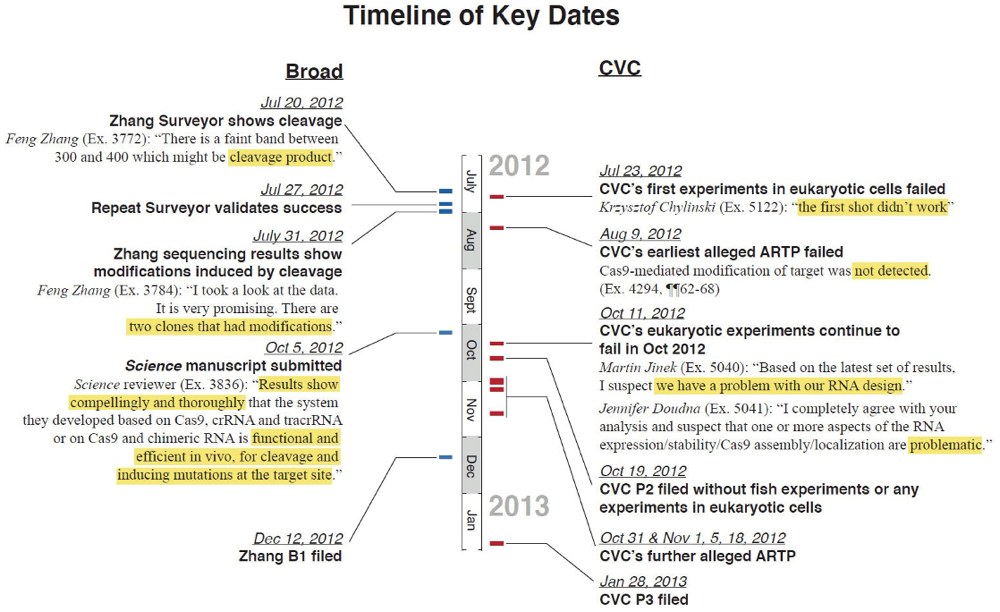

The Broad’s motion provided evidence that conceived of these applications and actually reduced them to practice prior to CVC. Part of its argument is that these methods are such that they cannot be conceived completely unless and until they have actually been shown to work (a situation termed “simultaneous conception and reduction to practice”), and that their dates of reduction to practice are earlier than CVC’s, providing the following timeline:

According to Broad, its invention of single guide molecule RNA embodiments of CRISPR methods for use in eukaryotic cells was the product of earlier work on CRISPR methods in eukaryotic cells using dual guide RNA molecule embodiments (which are not at issue in the interference).

As illustrated in the timeline, Broad asserts an actual reduction to practice on either July 20th or 27th (depending on when Broad's inventors can be found to have "recognized and appreciated [their] success"). While relying on their July 20, 2012 first actual reduction to practice date as set forth in its timeline, Broad also asserts conception of the method no later than June 26, 2012, when a collaborator disclosed the concept of single guide molecule RNA embodiments of CRISPR methods "heard about at a public conference."

While this date was later than CVC’s asserted date of such a conception, Broad’s motion makes the distinction that its inventors’ experience with other CRISPR methods in eukaryotic cells provide a basis for expecting these methods to work that CVC’s inventors did not have. These arguments were supported in Broad’s brief by statements successfully asserted in the first interference to the effect that CVC’s inventors did not appreciate that they had successfully reduced CRISPR to practice as easily, predictably, and routinely as they assert in their priority motion brief (a characterization CVC hotly contests, here and in the earlier interference).

There are a variety of procedural and evidentiary motions remaining in the interference, including motions for subpoenaing testimony from researchers associated with Broad that CVC believes have relevant evidence contrary to Broad’s current positions, all of which will take place between now and the final hearing scheduled some time (at the PTAB’s convenience) in May, 2021. While impossible to predict of course, it seems likely that the PTAB will need to decide whether CVC’s earlier conception, followed by diligent activities leading up to later reduction to practice, are enough to award priority to its inventors, or whether it is convinced that Broad is correct that only by showing actual reduction to practice could the invention be sufficiently conceived, in which case the PTAB should award priority to the Broad.

Kevin Noonan is a partner with the law firm McDonnell Boehnen Hulbert & Berghoff LLP and represents biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies on a myriad of issues. A former molecular biologist, he is also the founding author of the Patent Docs weblog, http://patentdocs.typepad.com/.