From the implant to the pill to intrauterine devices, there are multiple reliable options for preventing pregnancies. But many people prefer not to take a daily pill or have a device implanted, leaving them with contraceptive options that don’t fit their needs.

In the search for an “on-demand” oral birth control option, many women use emergency contraceptive drugs as their regular form of birth control without realizing that its efficacy at preventing pregnancy when used this way is not well understood. However, since emergency contraception works best to prevent pregnancy when taken as soon after unprotected intercourse as possible, researchers wondered if certain emergency contraceptives might work as on-demand contraceptive options.

“If I take [emergency contraception] one minute after unprotected intercourse, that's better than an hour later or a day later or three days later,” said Paul Blumenthal, an obstetrics and gynecology researcher at Stanford University. “What if I take it one minute before unprotected intercourse or one hour or one day or maybe three days?”

In a small pilot study, Blumenthal and Erica Cahill, a gynecologist and reproductive health researcher at Stanford University, and her team reported that the combination of two FDA-approved drugs, meloxicam (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) and ulipristal acetate (an emergency contraceptive), prevented ovulation (1). This drug combination could give people the on-demand contraceptive option they’ve been searching for.

“It's a very nicely done study on two agents that are known to work over the fertile time period in the cycle,” said Alison Edelman, a contraception researcher and clinician at Oregon Health and Science University who was not involved with the study.

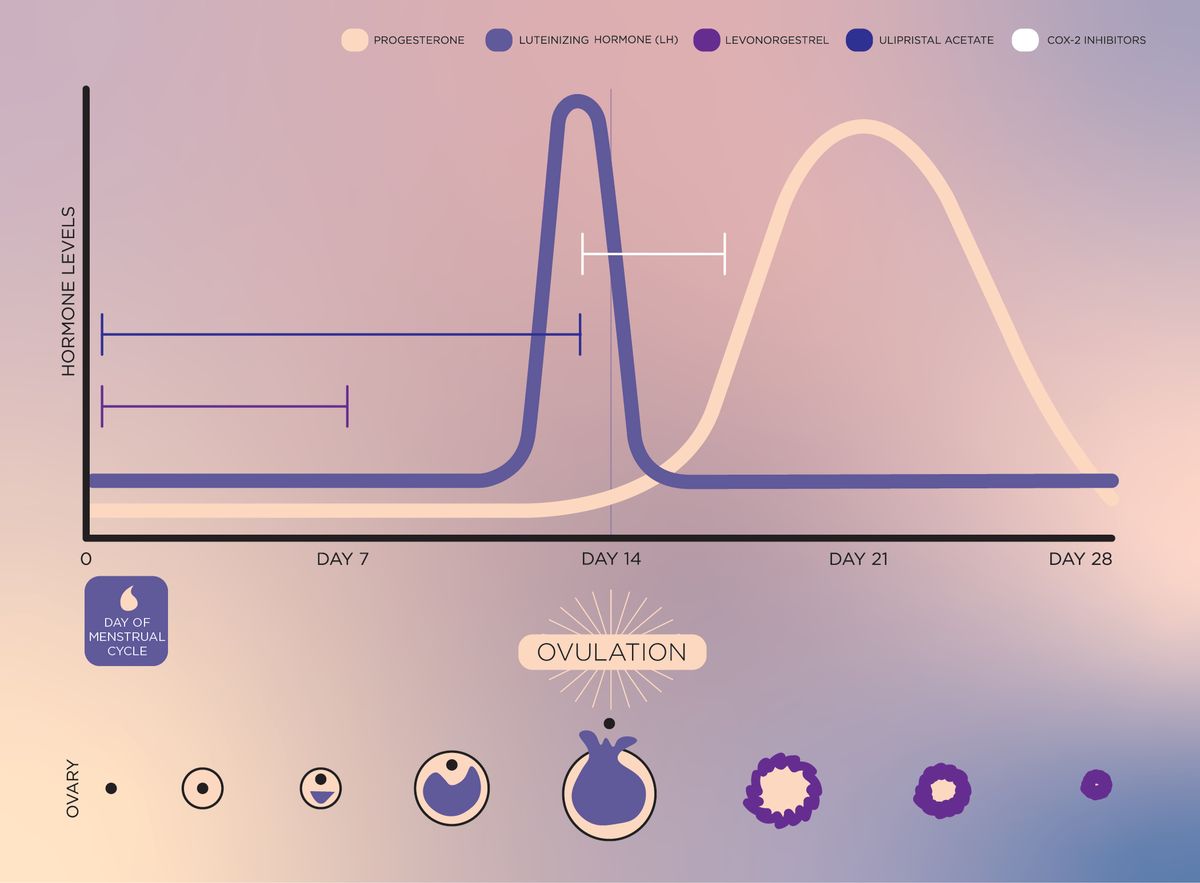

Before an egg is ready for fertilization, a sequence of intricately timed steps must occur. First, hormones from the hypothalamus signal to the pituitary gland, which in turn, releases hormones that act on the uterus and ovaries. In the ovaries, the premature follicle that will develop into the egg begins to mature. Once the follicle matures to a certain point, the pituitary gland releases a surge of luteinizing hormone (LH). This LH surge triggers a series of signaling events, and when LH levels drop, the ovary releases the mature egg. After ovulation, the cells in the ovary that supported egg maturation release high levels of the hormone progesterone, which inhibits any further release of LH from the pituitary gland.

Emergency contraceptive drugs act by inhibiting certain steps of this ovulation signaling cascade. For example, the drug levonorgestrel, which is a synthetic version of progesterone, inhibits ovulation by mimicking the rise in progesterone at end of the LH surge. If taken before the start of the LH surge, levonorgestrel works well to prevent ovulation, thus preventing pregnancy. But if LH levels have already begun to rise, levonorgestrel cannot stop ovulation from occurring.

Another emergency contraceptive drug, ulipristal acetate (UA), is a progesterone receptor modulator that prevents ovulation even if the LH surge has already started. However, if taken after the LH levels have peaked, it is no longer effective.

“We already know that emergency contraception works ahead of the luteal surge, so the question is, could it work right before ovulation is about to happen?” asked Cahill. “It would be great if we could block it at that point because that's probably the closest to ovulation moment.”

Research in humans suggests that cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors can prevent ovulation even after the peak of the luteal surge with a 25-30% efficacy (2). COX-2 inhibitors prevent the expansion of the ring of cells surrounding the mature follicle, a process called cumulus cell expansion. Inhibiting this process prevents ovulation.

Because UA can prevent ovulation from before the LH surge until LH peaks and COX-2 inhibitors act after the LH surge, Cahill and her team tested how well a combination treatment of UA and the COX-2 inhibitor meloxicam prevented ovulation through the rise and fall of the LH surge. They used ultrasound imaging to monitor participants’ follicle size and administered the drugs when follicles reached a diameter of 18 mm, the beginning of the fertile window. They then measured LH levels and follicle size throughout the rest of the fertile window.

“One challenge of the study was really trying to isolate that exact time at which the luteinizing hormone peak is occurring based on ultrasound findings,” said Cahill. It would have been more precise to measure LH levels in the blood, but “we weren't able to get the lab results back sooner than 24 or 48 hours, so that was challenging making sure we were in that window,” she added.

Cahill and her team reported that out of the nine women in the study, the UA and COX-2 inhibitor drug combination fully delayed or impaired ovulation in eight participants. While the researchers did their best to administer the combination treatment at the peak of the LH surge, only two out of the nine participants received the drugs after the peak of the LH surge. Of those two people, only one did not ovulate.

“The results here are promising, but maybe slightly overstating,” said Edelman. “We know that COX-2 inhibition does work in this space. But you can see that they're saying that they worked 50% of the time, but they only had a denominator of two… That could have been a random effect of their very small population.”

Cahill would like to perform a larger trial to validate these results, and she and her team would also like to test how well this drug combination works with people actually using it for contraception in a pregnancy trial.

“We [can] see what effect it has on menstrual cycles and side effects, but also efficacy. I think there's a lot of interest in using an on-demand, pericoital pill,” said Cahill. Such trials, where people accept the risk that they may become pregnant, will likely become more difficult to perform in countries like the United States as abortion access becomes more restricted.

Despite these difficulties, Cahill is eager to find a potential new contraceptive option for people who don’t have one. “It is so, so exciting to have any new ideas in this space because there are so many people that could be served by this,” she said. “That's really exciting to think about new ways of thinking about pregnancy prevention that work for different people and expanding the options.”

References

- Cahill, E.P. et al. Potential candidate for oral pericoital contraception: evaluating ulipristal acetate plus cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitor for ovulation disruption. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health 0, 1-5 (2022).

- Edelman, A.B. et al. Impact of the prostaglandin synthase-2 inhibitor celecoxib on ovulation and luteal events in women. Contraception 87, 352-357 (2013).